HOW?

How did our hero break his barrier?

All alone and with no one and nothing else, all Fred had was his case. And as the trial drew closer, Ernest came to visit Fred at Tanforan. Fred then gave Ernest a well-prepared, persuasive statement that summed up his views: that Japanese internment without a trial was unconstitutional. When the case ran, the judge was impressed with Fred, but still ruled him guilty of disobeying the order. Fred was sentenced to five years' probation; he would have to serve it in Tanforan. So Ernest and Fred's lawyer, a an named Wayne Collins, appealed to a higher court.

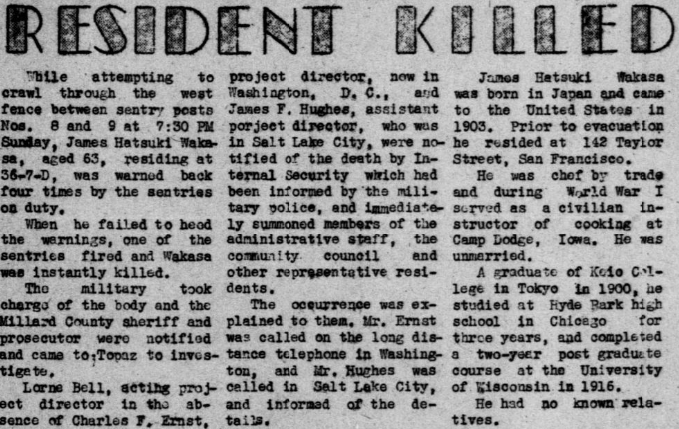

But soon after the trial, everyone at Tanforan was relocated to a new camp called Topaz. Completely isolated, the camp was often plagued by awful dust storms. It was wose than Tanforan, and were constantly reminded they were still inmates by incidents such as the day in April, 1943, when an elderly man walking near the fence was shot for "trying to escape".

It wasn't until December, 1943, when Fred heard again about the case. He had lost once again, but Ernest was appealing once more, this time to carry the case to the Supreme Court. By now the government, desperate for more workers, was letting Japanese Americans out of the camps to work. Fred got accepted. Finally, he was free.

But there was still much discrimination. Then, in December, 1944, Fred got a message from Ernest. He had lost his Supreme Court case. Fred couldn't believe it. How could they rule it was right? But they had, and Fred had to move on. There was nothing more he could do.

(Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress website, from their copies of the Tanforan Totalizer)

(Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress website, from their copies of the Topaz Times)